What are Compression Fractures of the Spine?

Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) occur when the bones of the spine (vertebrae) collapse or compress due to trauma, tumors, or a general loss of bone density. VCFs typically result from two underlying causes:

1) Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis: An imbalance in the quantity of cells that resorb and form bone leads to osteoporosis, or a weakening of bone structure, which can lead to fractures from minimal trauma. Osteoporosis is commonly called a “silent disease” by clinicians because there are no symptoms of this condition until a fracture occurs. While osteoporotic fractures represent fractures involving the spine, hip, humerus, and wrist, VCFs are the most common.

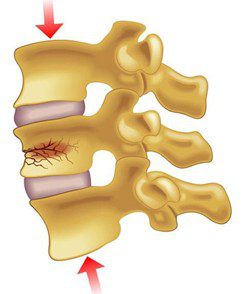

2) Trauma

Trauma: Falls, sports injuries, or vehicle accidents can all lead to VCFs. However, unlike VCFs that result from imbalances in bone strength, traumatic injuries cause direct mechanical damage to the vertebrae.

Affecting approximately 1 to 1.5 million Americans annually, VCFs predominantly impact older adults, particularly postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Specific risk factors include:

- Age: There is a significantly increased risk of VCFs for those over age 65 due to hormonal changes and an increased fall risk.

- Gender: Due to hormonal changes after menopause, women can experience reduced bone density, leading to VCFs. This is because postmenopausal women experience a decline in estrogen levels, which in turn can lead to a loss of bone density, or osteoporosis. In total, almost a fourth of postmenopausal women have had at least one VCF.

- Medications: Prolonged steroid use (e.g., prednisone), breast and prostate cancer treatments, and medications for acid reflux have all been linked with bone density loss, which can increase the risk of VCFs.

- Lifestyle: Smoking/vaping, excessive alcohol, poor nutrition, and inactive habits can accelerate processes that lead to osteoporosis and an increased risk for VCFs. In fact, smoking increases the risk of developing a spinal fracture by 32% in men and 13% in women. Likewise, excessive consumption of alcohol and poor nutrition severely hinders calcium and vitamin D absorption—two critical molecules for bone density and overall bone health.

Recognizing VCFs early is essential for preventing chronic pain, spinal deformity, and for improving quality of life.

Signs and Symptoms of Vertebral Compression Fractures

Only a third of patients with VCFs are able to obtain a clinical diagnosis. While not all VCFs cause symptoms, it is still critical to point out common signs and symptoms:

- Sudden, sharp back pains that worsen with movement and can worsen over time.

- Gradual loss of height: Each fractured vertebra can lose ~15-20% of its individual height when fractured.

- Postural changes, most notably increased curvature of the spine (kyphosis).

- Limited spinal flexibility.

Osteoporosis, one of the major drivers of VCFs, is a silent condition marked by low bone density and is a major risk factor for vertebral compression fractures. There are several tools available online that can help estimate your personal risk. One of the most commonly used is the FRAX calculator. It asks questions about risk factors like age, family history, and lifestyle to estimate your risk of fracture. Using FRAX can be a helpful first step in understanding your bone health, risk for osteoporosis, and knowing when to reach out to a healthcare provider. Calculate your FRAX score and take the results to your next visit with your general practitioner to establish a baseline.

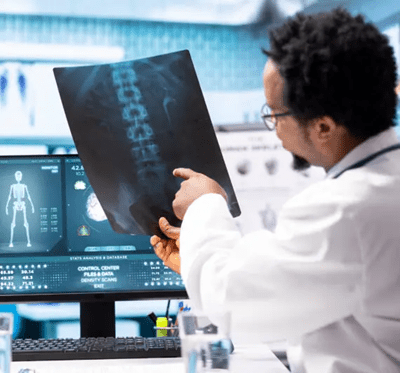

Diagnosing Vertebral Compression Fractures

Diagnostic imaging modalities commonly used for VCFs include:

X-rays:

- Typically used as an Initial screening tool.

- This modality can visualize vertebral collapse or wedge deformities.

MRI:

- Ideal for detecting recent/acute fractures.

- Can visualize soft tissue swelling, edema, and nerve involvement.

CT scans:

- Clarifies ambiguous or complex fracture patterns.

- Usually used in surgical planning and detailed anatomical assessments.

Treatment Options for Vertebral Compression Fractures Caused by Osteoporosis

Clinical management strategies for VCFs typically vary depending on severity and can be grouped into two major categories.

Conservative Management:

- Pain relief through medications like NSAIDs or acetaminophen may be prescribed for acute pain caused by VCFs. If the pain is severe enough, opioid analgesics may be prescribed for a short duration. A form of Calcitonin – a hormone that secretes calcium may also be administered, usually intranasally or subcutaneously.

- Temporary bracing to stabilize and reduce pain may also be recommended. Physical therapy and aqua therapy for muscle strengthening and mobility may be added to the routine.

Interventional Approaches:

- Vertebroplasty: Injecting medical-grade bone cement into fractured vertebrae to stabilize them.

- Kyphoplasty: Similar procedure to vertebroplasty but uses balloons to first elevate compressed vertebrae prior to cement injection.

- Surgical intervention: Required in severe fractures causing spinal instability or neurological compromise.

Importance of Secondary Fracture Prevention

Having a single vertebral fracture can significantly increase your risk for subsequent fractures, which is a phenomenon known as the “fracture cascade.” Specifically, approximately 20% of individuals with an initial vertebral fracture experience another within the next year. Each additional fracture can dramatically worsen quality of life, causing chronic pain, disability, and decreased independence. For instance, severe postural changes due to multiple secondary fractures can compress internal organs, cause cardiovascular strain, and lead to digestive issues. There may be implications for mental health as well. Decreased mobility due to compression factors can lead to depression, a sense of isolation, and an overall decreased quality of life.

Not only that, but untreated compression fractures are also associated with an increased risk of mortality if underlying causes such as osteoporosis are left untreated. Addressing this risk is a major, timely concern for healthcare professionals and scientists alike. The incidence of secondary fractures is expected to rise dramatically over the coming years, given that by 2050 the number of those over the age of 60 is expected to double. The volume of individuals expected to suffer from osteoporosis and compression fractures is slated to result in significant stress and cost to our healthcare system.

The Short and Long Term Effects of Untreated VCFs

- Short term: During the acute period, a VCF can cause a distinct pain profile. Upon directly experiencing a VCF, you can feel a sharp, sudden “knife-like” pain localized to the area of the spine where the fracture has occurred. This area may also be tender to the touch, and muscle spasms can occur. Over time, this pain can become dull and exacerbated by standing or walking, but better when lying down or at rest. Patients with VCFs report that bending over and lifting, such as a bag of groceries or a suitcase, can aggravate the pain caused by VCFs.

- Long term: If left untreated, the dull and aching pain and discomfort caused by VCFs may persist and worsen as the bone collapses, nearby nerves become irritated, and muscles continue to fatigue. This chronic pain and deformity can lead to a forward curvature of the spine (“hunchback”) which has a negative effect on the surrounding discs. These compounding changes in the biomechanics of the spine lead to an overall functional decline, an increased dependence on others, a higher likelihood of hospitalization, and hindered motion.

However, not all VCFs are the same. Many individuals suffer from asymptomatic or mild symptoms, which can make it more difficult to identify and treat VCFs. Yet, the long-term effects of asymptomatic VCFs can still be equally as consequential. For instance, patients can still develop functional limitations and are at a higher risk of subsequent symptomatic VCFs, deformity, and increased mortality. Missed opportunities to diagnose osteoporosis are also a concern in asymptomatic patients, as an undiagnosed global loss of bone density leads to a greater risk of fractures in other areas of the body, such as the hip.

How Can I Prevent Secondary Fractures Due To Osteoporosis?

Pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis is the best way to prevent secondary fractures. Medications can therefore be broken down into three distinct categories, depending on the severity of osteoporosis.

1st Tier Drugs:

For mild to moderate osteoporosis, these treatments are given for 3-5 years, daily, and by oral or IV infusion.

- Bisphosphonates (Alendronate, Zoledronic acid) can stabilize bone density by slowing the loss of bone mass.

- Raloxifene is given to postmenopausal women with osteoporosis because it is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that works to increase estrogen, which works to preserve bone density.

2nd Tier Drugs:

For moderate osteoporosis, this medication is administered every 6 months by subcutaneous injection.

- Denosumab (Prolia) has been found to increase bone density by 5%-10% each year by neutralizing cells in the body that break down/absorb bone tissue called osteoclasts.

3rd Tier Drugs:

For severe osteoporosis, these medications are given daily or monthly for 1-2 years via subcutaneous injection.

- Teriparatide (Forteo) is a parathyroid hormone analog that improves bone density by stimulating new bone formation, by approximately 10% each year.

- Abaloparatide (Tymlos) is a parathyroid hormone-related protein analog that stimulates bone formation, increasing bone density and strength by approximately 6% each year.

- Romosozumab (Evenity) stimulates bone formation and reduces bone breakdown and has been found to increase bone density by approximately 15% after 12 months of treatment.

Nutrition and Lifestyle can also play a large role in strengthening bones are preventing secondary fractures:

- Adequate calcium (1000–1200 mg/day) and vitamin D (800–1000 IU/day).

- Regular weight-bearing exercises (e.g., walking, resistance training).

- Limiting alcohol and quitting smoking can prevent further bone weakening.

Fall prevention is critical for avoiding secondary fractures. Common methods to reduce falls include:

- Home safety measures: installing grab bars and removing tripping hazards.

- Balance training exercises such as yoga, tai chi, and specific physiotherapy exercises.

- Using assist devices if unsteady (cane, walker, or walking sticks)

Final Thoughts

Vertebral compression fractures can significantly impact quality of life, yet early detection, appropriate treatment, and dedicated secondary fracture prevention strategies can dramatically reduce further risks. Proactive spine health management through proper medication, nutrition, physical activity, and regular screenings is critical. While the prospect of long‑term medication may seem daunting, it ultimately offers a scientifically proven path to stronger bones, reduced pain, and, at the end of the day, preserved independence for those who would otherwise suffer. Talk with your healthcare provider today to develop a personalized plan to protect your spine health and maintain your quality of life.