If you’ve ever felt a sharp, shooting pain that starts in your lower back or buttock and travels down your leg, you may have experienced sciatica. This condition is surprisingly common—affecting up to 40% of people at some point in their lives—and while the pain can be frightening, there are effective treatments and ways to prevent future problems.

What Exactly is Sciatica?

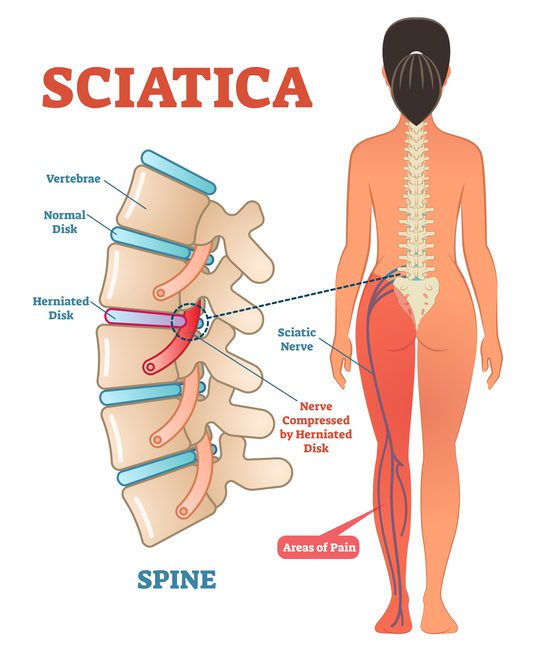

Sciatica isn’t a disease by itself—it’s a set of symptoms caused by irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve.

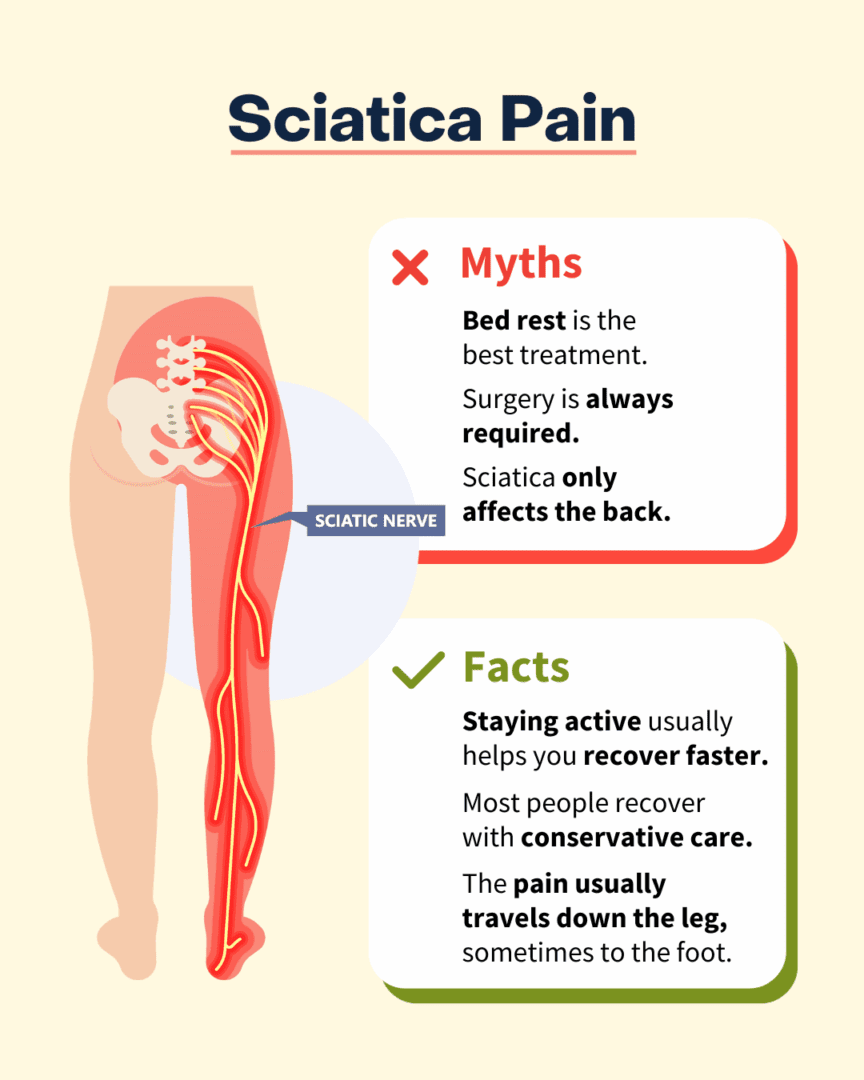

This nerve is the largest in your body, starting in your lower spine, traveling through your buttock, and branching all the way down into your legs and feet. Because the nerve is so long, problems at the spine can cause pain anywhere along the pathway.

Why Does Sciatica Hurt So Much? (The Nerve Pathway)

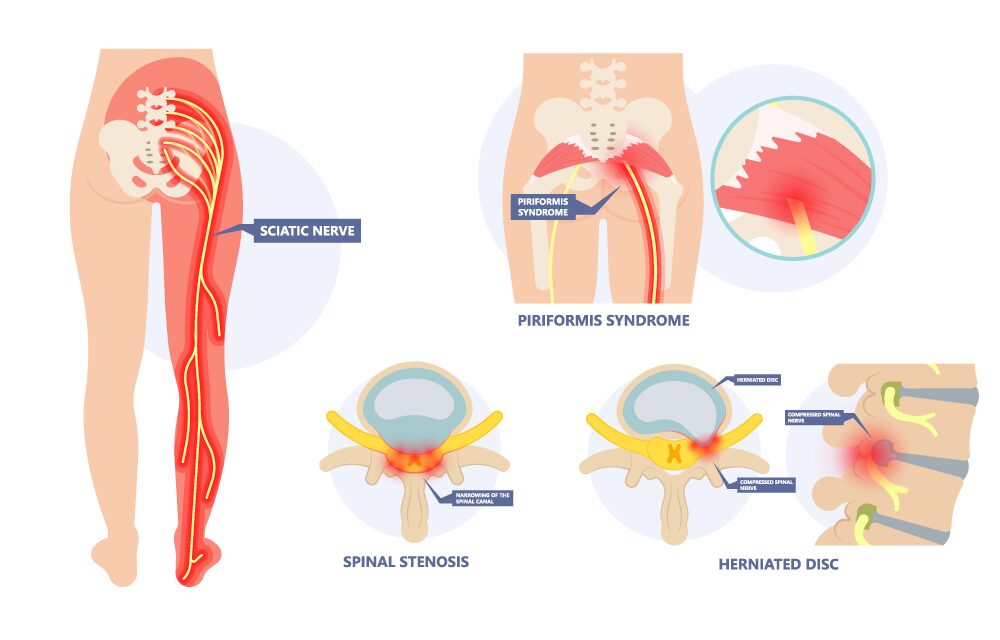

The sciatic nerve is formed from several small nerves that exit the lower spine. Together, they form one thick nerve that runs down the back of each leg.

That’s why sciatica pain can show up on the buttock only, down the entire leg, even into the foot and toes.

The pain may be sharp, burning, or feel like an electric shock. Some people also notice numbness, tingling, or weakness.

What Causes Sciatica?

The most common causes include:

- Herniated disc pressing on a nerve root

- Spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal)

- Spondylolisthesis (a vertebra slipping forward)

- Arthritis or bone spurs

- Piriformis syndrome (a tight buttock muscle pressing on the nerve)

- Less common but serious causes include trauma, infection, or tumors.

Conditions That Can Be Confused with Sciatica

Not every leg pain is sciatica. Other conditions can mimic it, such as:

- Hip arthritis (pain in the groin/thigh, not shooting down the leg)

- Peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage from diabetes or other causes)

- Vascular disease (leg cramps from poor circulation)

- Sacroiliac joint problems (pain in the buttock region)

That’s why getting the right diagnosis matters.

How Do Doctors Diagnose Sciatica?

Diagnosis usually starts with a good medical history and physical exam . Doctors will test reflexes, strength, and sensation. If symptoms are severe or don’t improve, imaging and tests may include:

- MRI – the best tool for looking at discs, nerves, and spinal stenosis

- X-rays or CT scans – more useful for bone problems

- EMG (electromyography) – tests nerve function in the leg muscles

Non-Surgical Treatments (First Line for Most Patients)

The good news? Most people get better without surgery. Treatments may include:

- Medications – NSAIDs, muscle relaxers, targeted nerve medicines, and acetaminophen for pain relief

- Physical therapy – gentle stretching, core strengthening, and posture correction

- Heat and ice therapy

- Activity modification – avoid long periods of sitting or heavy lifting, but keep moving

- Steroid injections – to reduce inflammation around the nerve

Quick fact: About 80–90% of patients improve within a few weeks to months of conservative care.

When Surgery Becomes an Option

Surgery may be recommended if:

- Pain does not improve after 6–12 weeks of non-surgical treatment

- You have progressive leg weakness

- You develop “red flag” symptoms such as loss of bladder or bowel control (a medical emergency called cauda equina syndrome)

Common surgical procedures include:

- Microdiscectomy – removing the herniated disc

- Laminectomy – widening the spinal canal to relieve stenosis

Most patients experience significant pain relief and improved function after surgery—especially when it’s done before permanent nerve damage occurs.

Why Timing Matters

Nerves can recover, but only to a point. Delaying treatment in severe cases can lead to permanent numbness, weakness, or loss of function. If symptoms are worsening, don’t wait—see a doctor promptly.

Prognosis: What to Expect Long-Term

Without surgery: Many patients recover completely, but flare-ups can happen.

With surgery: Pain often improves faster, and surgery reduces the risk of long-term nerve injury when done at the right time.

Most people return to normal activities, but some may need to adjust work, exercise, or lifestyle habits to protect their spine. Preventing a recurrence through core strengthening is key for the long term.

What to Watch for After a First Episode

Once you’ve had sciatica, you’re at higher risk for another episode. Warning signs include:

- Pain returning or spreading

- Increasing numbness or weakness

- Bowel or bladder changes (urgent medical attention needed)

Can Sciatica Be Prevented?

Not all cases can be prevented, but you can reduce your risk:

- Stay active – regular stretching and strengthening for your core

- Practice good posture when sitting, standing, and lifting

- Maintain a healthy weight to reduce pressure on your spine

- Avoid prolonged sitting – take breaks to move

- Use proper lifting techniques – bend at your knees, not your waist

References:

Stafford MA, Peng P, Hill DA. Sciatica: a review of history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and the role of epidural steroid injection in management. Br J Anaesth. 2007.

Peul WC, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007.

Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2015.

Kreiner DS, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014.