By Michael Steinmetz, MD, Cleveland Clinic

Introduction

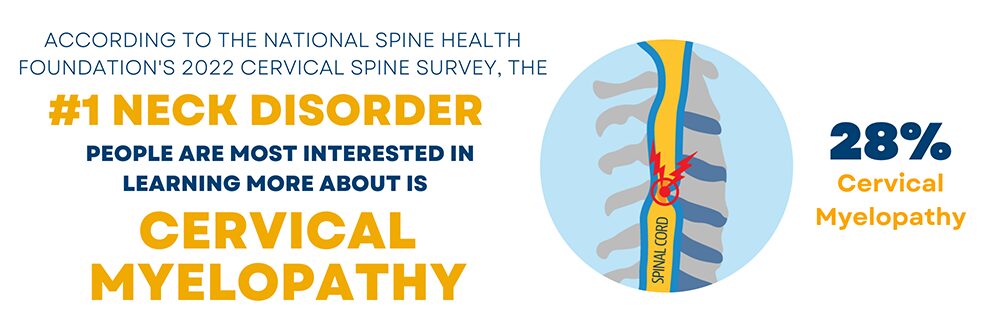

Cervical myelopathy describes a neurological condition most often associated with cervical stenosis. Cervical spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal which decreases the space available for the spinal cord in the neck. Cervical spinal stenosis is a common finding on imaging of the cervical spine, but does not always cause symptoms, which is a very important distinction to be understood. The diagnosis of cervical myelopathy is only made when the narrowing or “squeezing” of the spinal cord causes symptoms.

Symptoms

The symptoms related to myelopathy are fairly typical. Classically, a patient would present with a complaint of decreased balance or feeling like they walk as if they are “drunk,” numbness and tingling in both hands, and a decreased ability to perform fine functions with their hands. They may describe difficulty with typing or handwriting, buttoning buttons, zipping zippers, etc. Neck pain may be present, but not always. Patients without neck pain are often surprised when they are told the issue is in their cervical spine.

Physical Exam Findings

There are classic findings on physical exam that confirm the diagnosis of myelopathy. As mentioned previously, not all patients with cervical stenosis have symptoms related to the imaging findings and the detection of symptoms is often difficult for patients, so a detailed physical exam by an expert is necessary to observe signs of myelopathy. Abnormal findings on physical exam include:

- The presence of hyperreflexia (overactive reflexes)

- Increased deep tendon reflexes compared to normal or baseline

- Hoffman’s sign (observed with a finger test)

- Babinski sign (observed with a foot test)

- Clonus (involuntary muscle contractions, often seen in the ankle)

- A loss of balance, texted by assessing the gait

Natural History

The natural history of this condition is very important to understand. Most patients worsen slowly over time, which can make it difficult for patients to identify a change. The worsening does not occur over days, but rather months. Some stay stable for a very long period of time. A very small percentage of patients may rapidly worsen, but this is rare. Myelopathic symptoms do not come and go, so if a decline occurs over a period of time, one is not expected to have spontaneous improvement in function.

Treatment

Surgery to relieve the pressure on the spinal canal (decompression) is the definitive treatment for progressive cervical myelopathy. Medications and other alternative treatments are not effective or based in science. Surgery, however, is not required in all patients. If symptoms are mild and not progressing, the patient can simply be followed with regular check-ups to assess signs and symptoms. Surgery is typically reserved for those who present with more severe symptoms or if there is a worsening of symptoms.

If surgery is planned, multiple options exist. Despite the many surgical approaches, the goal is always the same, to decompress the spinal cord by relieving the compression and giving it more room. Surgery can be done through the front of the neck (anterior), through the back (posterior), or even both. The approach is determined by the surgeon based on a number of factors: age of the patient, number of spinal levels causing compression, cervical spine alignment, and presence or absence of spinal deformity. Surgery through the front of the neck is called anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) and is commonly performed at 1 or 2 spinal levels (Figure 1). When multiple levels are involved, surgery is more common through the back of the neck. If normal spinal alignment is present, a laminoplasty may be performed (Figure 2). If malalignment is present, laminectomy and fusion may be performed (Figure 3). A surgeon’s preference and training will also guide treatment.

Controversy exists in treating asymptomatic spinal stenosis. An example of this would be a patient who had an MRI of the cervical spine for a non-neurologic reason, perhaps neck pain. The MRI demonstrates spinal stenosis, BUT the patient does not have any complaints of myelopathy (described above). A minority of physicians will urge surgery to be done urgently. The patient is often told that they are in imminent danger of being paralyzed and are frightened into having surgery.

At our center, we have had a number of patients emergently added to our clinic schedule or requesting consultation in the emergency room due to spinal stenosis and risk of paralysis. The reality is, we rarely operate in this scenario. We always stress to our patients and trainees that we only operate on patients with signs and symptoms of myelopathy and not on the imaging findings alone. It is interesting that when you consider the risk of paralysis in an asymptomatic patient, they have a greater chance of paralysis if they undergo immediate surgery versus walking out of the office and living a normal life. Patients are shocked but understand this explanation.

Postoperative Expectations

The overall goal of surgery is to stop the progression of the symptoms (worsening balance and coordination). A surgeon will often tell a patient that a successful surgery prevents symptoms from worsening, even if they do not improve. In reality, most everyone improves, however the degree of improvement is variable and hard to define for a patient planning to undergo surgery. There are some factors which are known to negatively impact the chance of improvement. These include advancing age, long duration of symptoms, and severe symptoms at the time of surgery. Physical and occupational therapy will be utilized at some point during the recovery process to help regain function.

Summary

Cervical spinal stenosis is the narrowing of the space for the spinal cord in the neck, is somewhat common, and can result in the neurologic condition known as cervical myelopathy. The natural history is that of a slow progression over time with periods of stability. Surgery is offered if symptoms are present and progressing, or if they are severe at the time of presentation. Multiple surgical options exist based on a number of patient factors and surgeon experience. The overall goal of surgery is to relieve the compression on the spinal cord. A halt in the progression of the symptoms should be expected and most will even improve after surgery. The risks of surgery are small and outweigh the risks of the natural history of cervical stenosis causing progressive myelopathy.