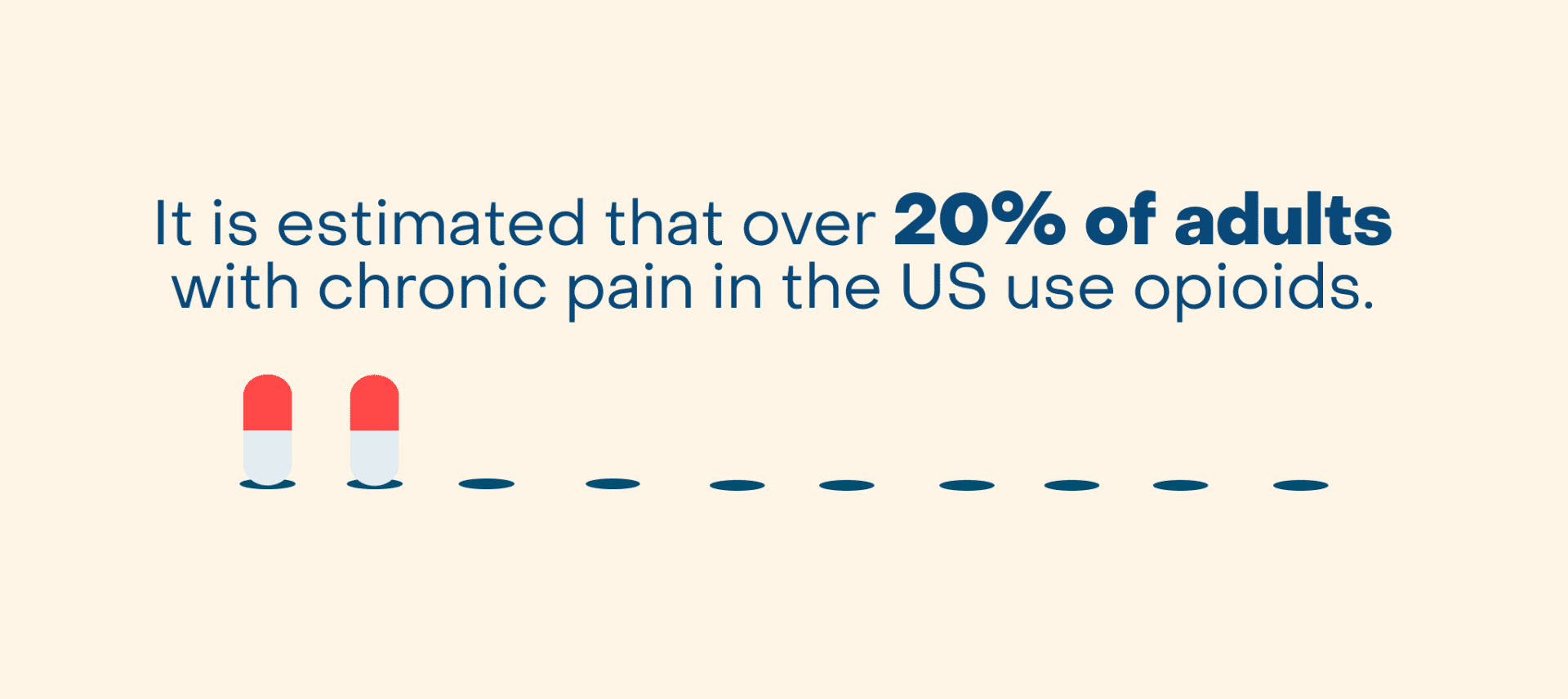

Back pain is one of the most common reasons people visit the doctor. Four out of five people experience back pain at some point in their lives, and when back pain continues beyond 3 months, it becomes chronic. Chronic low back pain is one of the most common types of chronic pain in adults worldwide, and always ranks highest for years lived with a disability. It is estimated that over 20% of adults with chronic pain in the US use opioids.

With the rate of opioid use rising, it is important to understand the risks of both short-term and long-term opioid use. In 2022, nearly 9 million Americans reported misusing prescription opioids in the past year, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioids are highly addictive substances, which can be difficult to stop once started. People suffering from back pain should know that there are effective alternatives to opioid use that can help reduce and manage pain.

How Opioids Work

Opioids, commonly known today as narcotics, provide short-term relief from severe pain. Throughout history, opioids have been utilized for their pain-relieving properties. Opioid use for pain relief dates back to 3400 BC, when opium poppies – nicknamed “the joy plant” – were cultivated in Southwest Asia for that purpose. They were first used in the modern medical setting in place of anesthesia to relieve pain during surgical procedures.

Opioids function by binding themselves to proteins (pain receptors) in the brain, allowing the brain to block feelings of pain throughout the body. People taking opioids can feel a range of responses, from relaxed or drowsy to euphoric.

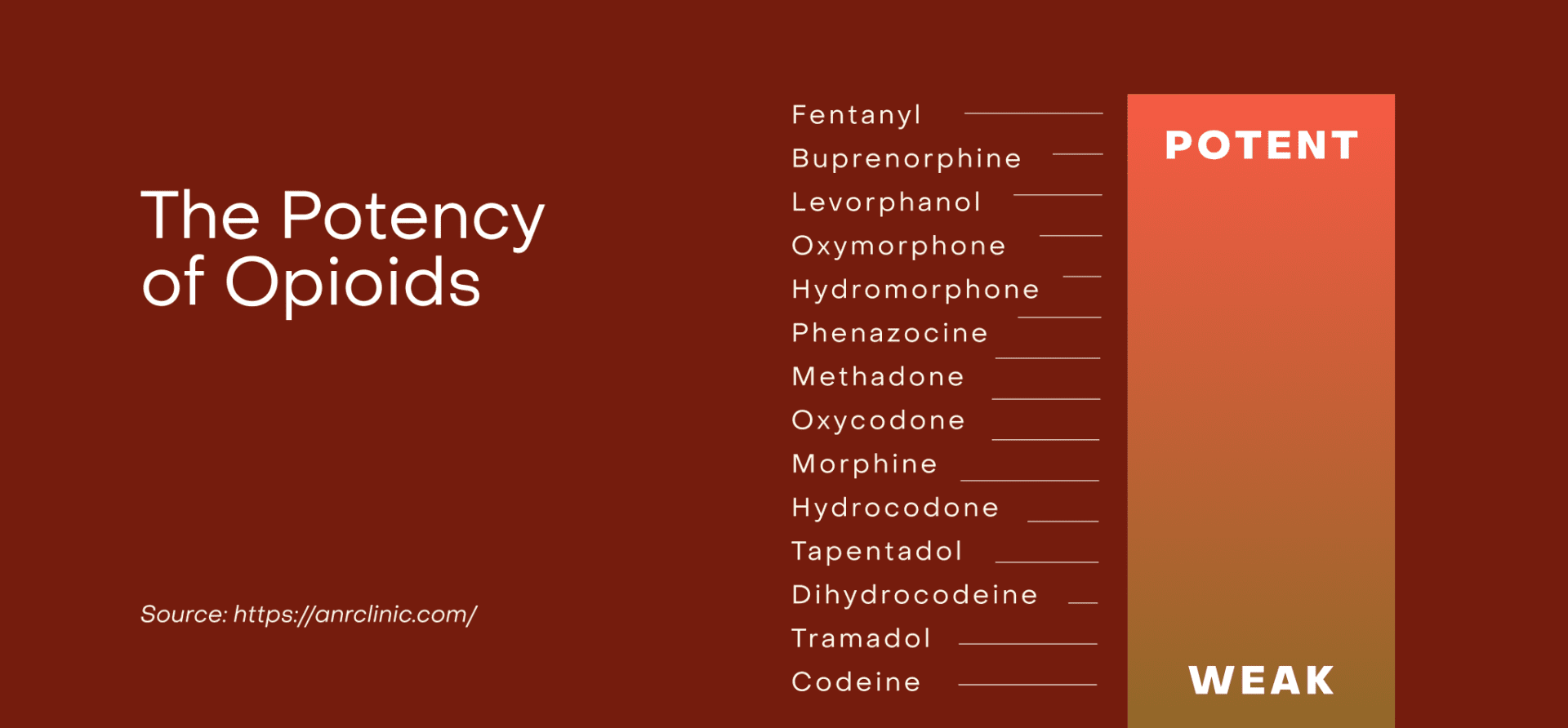

The most widely prescribed opioids are: hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, and codeine.

But opioids aren’t as good at relieving back pain as commonly believed. In studies, opioids were shown to relieve back pain in only about 10 out of 100 people. They usually don’t work any better than NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, and come with greater potential side effects and risks. While the pain relief is limited, the euphoric feelings may contribute to a sense that pain is relieved.

Is it Safe to Take Opioids for Back Pain?

With the proper prescription and monitoring, opioids can be a safe, short-term option for acute back pain relief. However, it’s essential to consider the benefits of opioids and weigh them against the risks of taking these drugs.

While opioids can relieve acute back pain temporarily, they don’t address the underlying cause of the problem. Getting to the bottom of the pain and getting proper treatment can prevent acute pain from transitioning into subacute pain and then becoming chronic pain. And most importantly, no matter what the cause is, they’re not a good long-term solution and can come with serious health risks over time.

Generally, it is recommended that other treatments are explored prior to utilizing opioid prescriptions. Research has found that while opioids may offer pain relief for some, they are not typically superior to non-opioid pain relievers, have less positive impacts on the body, and can cause serious side effects in many patients.

What are the Risks of Taking Opioids for Back Pain?

The short-term side effects of using opioids can include: constipation, itchiness, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, respiratory problems, confusion, depression and dizziness.

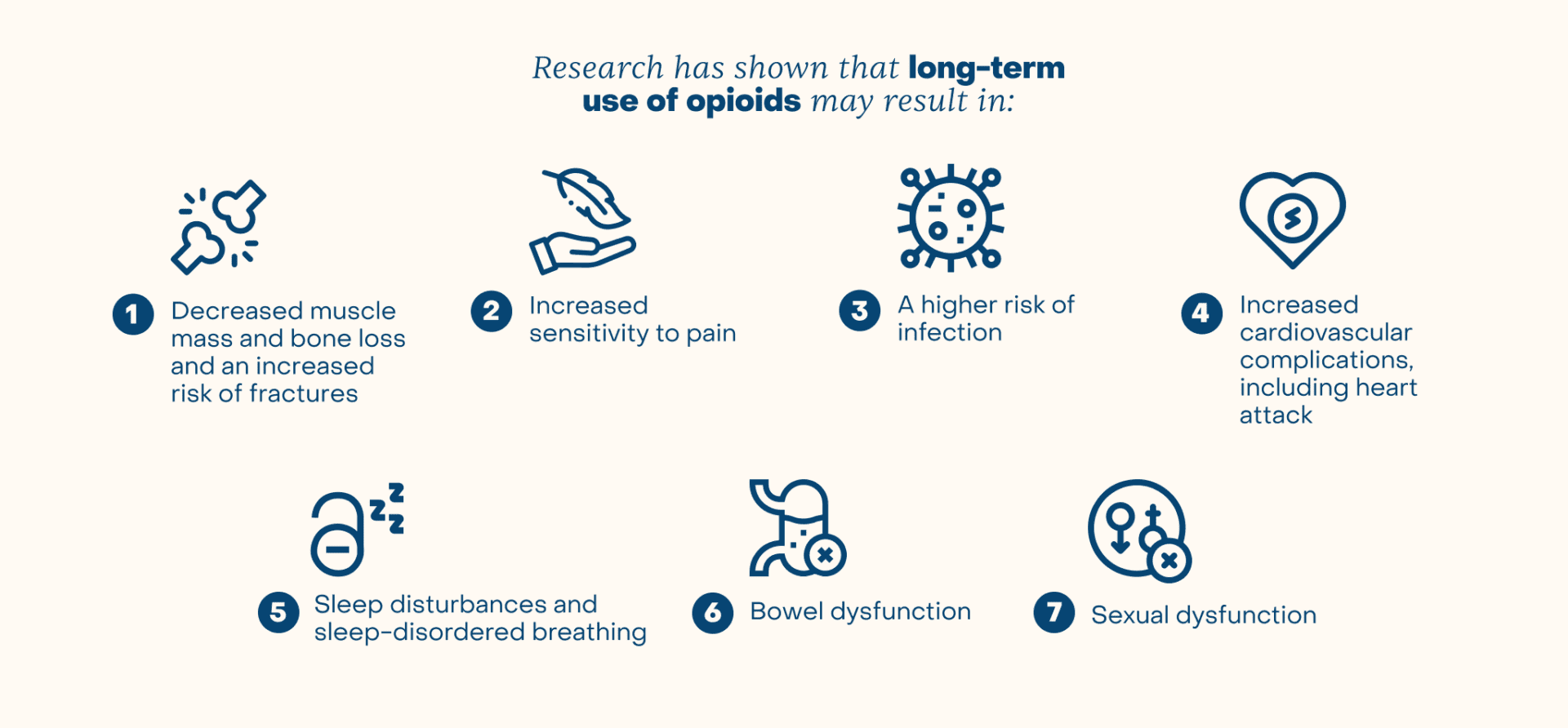

In addition to the adverse effects associated with opioid dependency and addiction, repeated use of opioids can have significant effects on the body’s systems, including the endocrine, immune, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and neural systems. Research has shown that long-term use of opioids may result in:

- Decreased muscle mass and bone loss and an increased the risk of fractures

- Increased sensitivity to pain

- A higher risk of infection

- Increased cardiovascular complications, including heart attack

- Sleep disturbances and sleep-disordered breathing

- Bowel dysfunction

- Sexual dysfunction

Additionally, people who repeatedly take opioids are at higher risk of accidental overdose. The World Health Organization found that close to 80% of deaths attributable to drug use are related to opioids.

Taking Opioids for Surgical Recovery

Medical professionals often prescribe opioids to help patients manage their pain following spinal surgeries. Pain is a common symptom being treated by spine surgery, and is often very severe. Then, spine surgery itself can add to the pain before symptoms resolve during recovery. This is a challenging scenario. The ultimate goal is to achieve enough pain control to recover properly from spine surgery, but limiting the duration of opioids to avoid tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

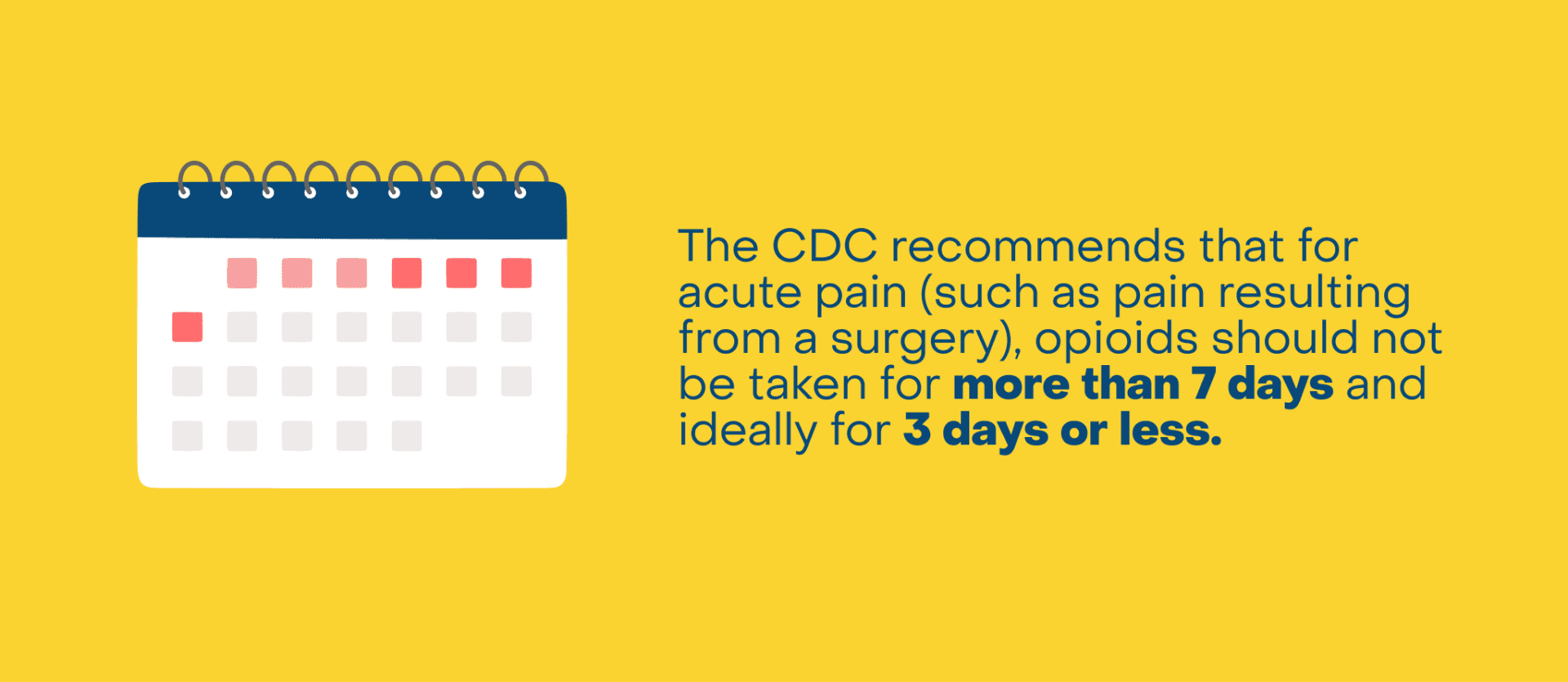

The CDC recommends that for acute pain (such as pain resulting from a surgery), opioids should not be taken for more than 7 days and ideally for 3 days or less. Surgeries differ greatly on the amount of pain they are associated with, making a general guide difficult to strictly follow, particularly in the field of spine surgery. Yet, research published in the Journal of Spine Surgery has shown as many as 38% of patients are still using opioids one year after elective spine surgery.

Additionally, patients who are already taking prescription opioids before surgery often need significantly higher doses of opioids after surgery and for a longer period of time. Because of this, opioids should be used carefully in relation to surgeries, focusing on specific patients’ needs and tailoring their prescriptions accordingly. It is important to consider interdisciplinary collaboration in these scenarios, including consultation with pain specialists, to determine the safest path forward.

The opioid epidemic in the U.S. has led prescribers to reevaluate postoperative pain control particularly in the field of spine surgery, where postoperative analgesia requirements and consumption have historically been high. Surgeons consider factors such as preoperative opioid consumption, smoking status, patient age, and magnitude of surgery when prescribing opioids, aiming to minimize opioid exposure while effectively managing pain.

One study showed that at 90-days after elective spine surgery, the percentage of unused opioids was over 45% – suggesting that the modern elective spine surgery patient is using less opioids than prescribed and that pain can be managed effectively in other ways.

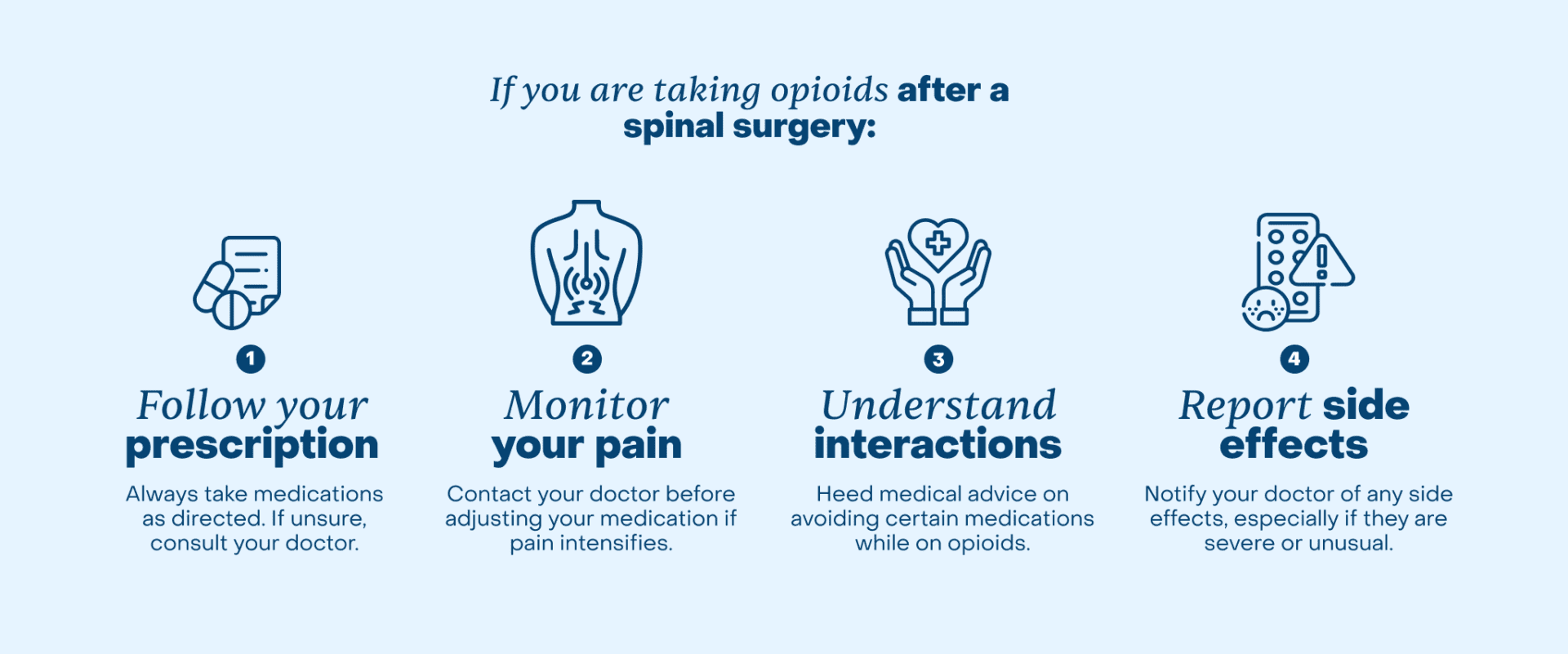

If you are taking opioids after a spinal surgery:

- Follow your prescription: Do not take more than prescribed. Patients who are unclear about their prescription should ask their doctor for clarification.

- Monitor your pain: In the case of severe pain, your doctor should be consulted before any changes are made to the dosage you are taking. Do not self-prescribe.

- Understand interactions: Follow your doctor’s advice on other medications to avoid while using opioids. This can prevent dangerous interactions that can enhance side effects, reduce the effectiveness of pain management, and increase the risk of addiction and overdose.

- Report side effects: Common side effects of taking opioids after surgery include nausea, vomiting, constipation and impaired thinking skills. Inform your doctor if you experience unusual side effects, like trouble breathing.

Safe Dosage of Opioids

Safe doses of opioids will differ depending on the patient’s pain level, medical history, height and weight. Doctors may also use screening procedures when prescribing doses, like the Opioid Risk Tool. This screening consists of five questions that help determine a patient’s risk of opioid abuse by assigning a risk score.

For general acute pain, doctors prescribe opioids for the number of days they anticipate the patient will experience significant pain, usually 5-7 days. Injuries or surgeries causing pain for less than five days may not require opioids at all. After spine surgery, opioids are initially prescribed based on what was needed during the hospitalization after surgery, then adjusted over time. The CDC’s dosage guidelines recommend staying under 50 MME/day. Doses greater than this amount increase the patient’s risk of overdose significantly, while the relief from the medication increases only by a miniscule amount.

It’s important to safely dispose of any excess medication. Keeping these opioids at home could lead to addictive behaviors or endanger children or other members of the family. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) recommends that patients dispose of unused prescription opioids by bringing them to DEA-registered collection sites, or using mail-back programs. Collection sites are often located at pharmacies. Alternatively, the DEA offers some instances where disposing of unused medications by flushing them down the toilet may be accepted, or disposal in the trash after mixing them with unpalatable substances, such as cat litter.

Fentanyl and Opioids: The Deadly Side of Pain Relief

Understanding the difference between prescription opioids and illegal opioids is essential for proper pain management. The only safe approach to taking opioids is through a doctor’s prescription. One opioid that is particularly dangerous without proper supervision is fentanyl. Fentanyl is a type of opioid that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine.

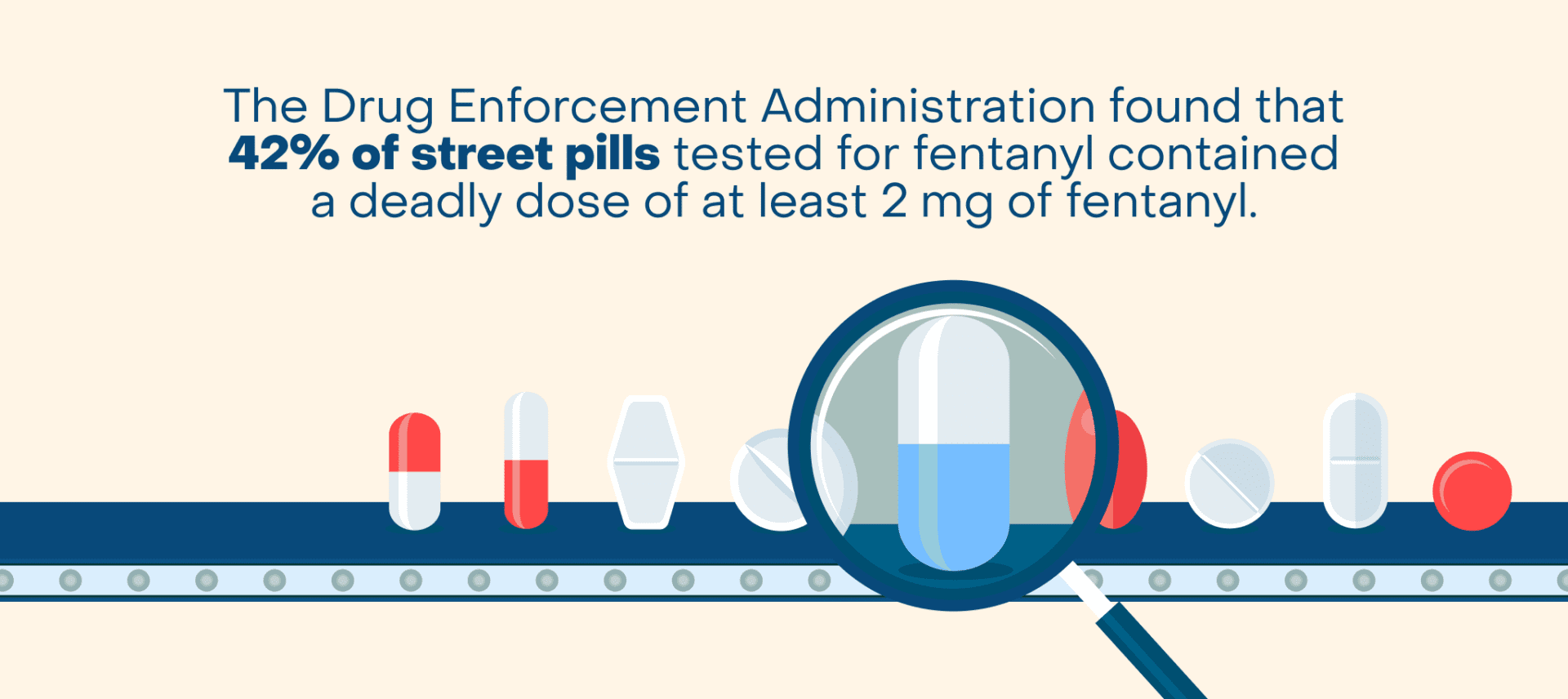

Doctors sometimes prescribe fentanyl to treat severe pain. On the other hand, unlawfully developed fentanyl is distributed through illegal drug markets and comes with a significantly higher risk factor. This type of fentanyl is hazardous due to its high potency and lack of regulation. This significantly increases the risk of overdose and death, since fentanyl only requires 2 milligrams (like a pinch of salt) to be lethal.

The Drug Enforcement Administration found that 42% of street pills tested for fentanyl contained a deadly dose of at least 2 mg of fentanyl.

Opioids should NEVER be taken without a doctor’s prescription and legitimate pharmacy dispensing them.

Will I Get Addicted to Opioids if I Use Them For Back Pain?

Opioids are addictive by nature, and anyone who uses opioids is at risk for addiction, regardless of age, gender, race or other demographics. One study showed that controlled medications are much more likely to be prescribed to individuals living in low income white communities.

However, steps can be taken to avoid addiction, such as only taking exactly what your medical professional prescribes, and not taking opioids for longer than they are needed. It is also important to manage pain control expectations. Severe pain can be made more manageable by taking opioids for a short duration, but pain should not be expected to be entirely eliminated. This unrealistic expectation of complete pain resolution often leads to taking higher than needed doses of opioids.

According to the American Medical Association (AMA), an estimated 3% to 19% of people who take prescription opioid pain medications develop an addiction to them. Addiction to opioids results from changes in the brain that develop after chronic opioid abuse, and are very complex. There is also a genetic predisposition that often contributes to addiction potential.

Dealing With Opioid Withdrawal

Withdrawal from opioids is a powerful factor that drives opioid dependence and addiction. It is not recommended to stop taking chronically used opioids abruptly. Tapering chronic opioid use should always be done under the management of a medical professional. Typically, a doctor will slowly reduce the prescribed opioid dosage in a day-by-day or a week-by-week tapering plan.

Opioids can be weaned off through both fast tapering and slow tapering. Fast tapering is a more sudden dosage reduction done over a few days to a week. This method may cause more severe withdrawal symptoms for those taking opioids long-term. Slow tapering is a gradual dosage reduction over one to three weeks. While this will cause less severe withdrawal symptoms, patients can still struggle.

Managing withdrawal symptoms during opioid dosage reduction can be challenging, but various strategies can help alleviate these effects. Drinking lots of fluids to avoid dehydration, doing mind-body therapies to help with relaxation, and staying in constant communication with a doctor can make the process much more manageable.

Alternatives to Opioids

There are many alternatives to opioids for managing pain. Here are some common alternatives:

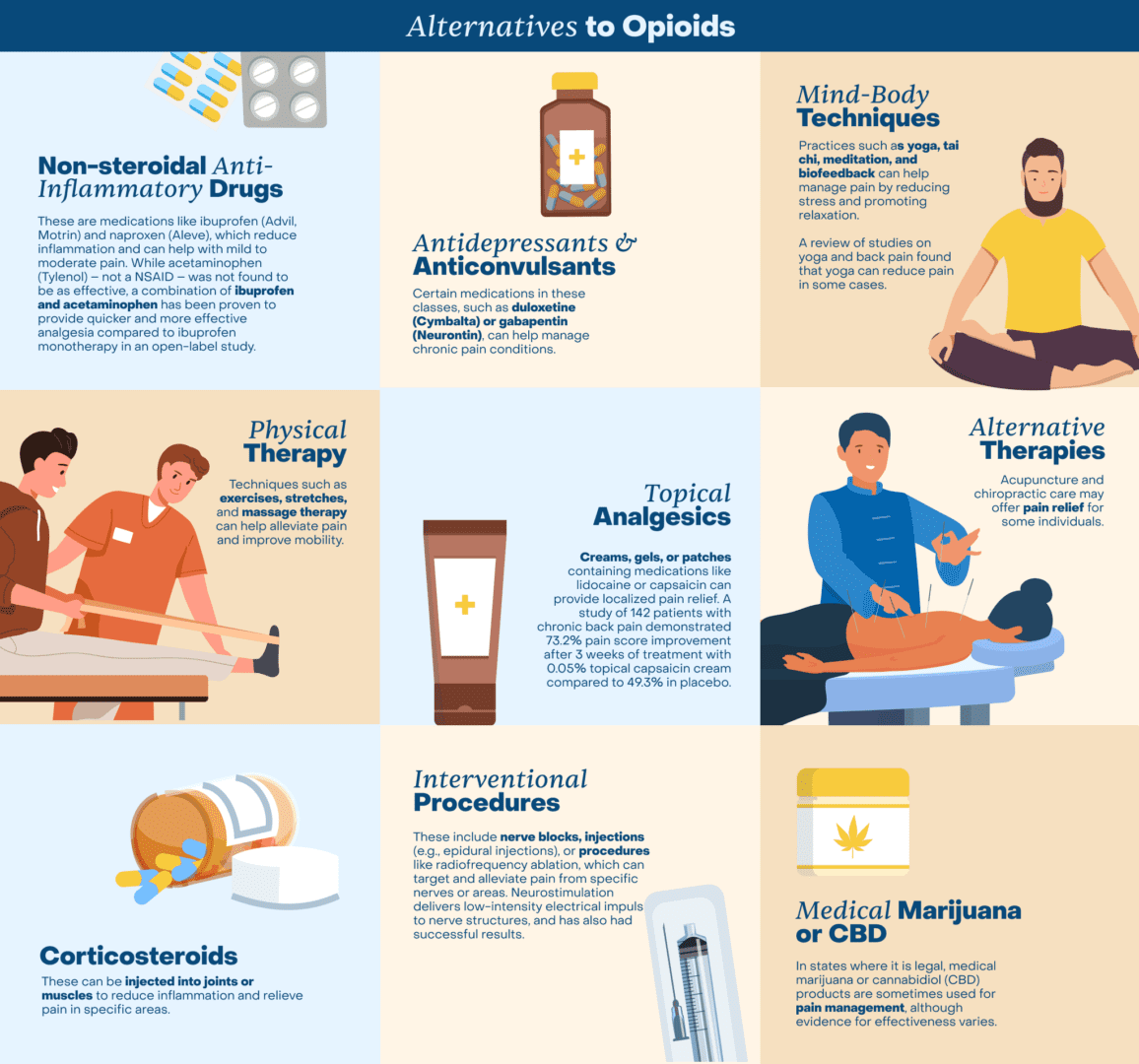

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): These are medications like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve), which reduce inflammation and can help with mild to moderate pain. While acetaminophen (Tylenol) – not a NSAID – was not found to be as effective, a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen has been proven to provide quicker and more effective analgesia compared to ibuprofen monotherapy in an open-label study.

- Physical Therapy: Techniques such as exercises, stretches, and massage therapy can help alleviate pain and improve mobility.

- Corticosteroids: These can be injected into joints or muscles to reduce inflammation and relieve pain in specific areas.

- Antidepressants and Anticonvulsants: Certain medications in these classes, such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) or gabapentin (Neurontin), can help manage chronic pain conditions.

- Topical Analgesics: Creams, gels, or patches containing medications like lidocaine or capsaicin can provide localized pain relief. A study of 142 patients with chronic back pain demonstrated 73.2% pain score improvement after 3 weeks of treatment with 0.05% topical capsaicin cream compared to 49.3% in placebo.

- Interventional Procedures: These include nerve blocks, injections (e.g., epidural injections), or procedures like radiofrequency ablation, which can target and alleviate pain from specific nerves or areas. Neurostimulation delivers low-intensity electrical impulses to nerve structures, and has also had successful results.

- Mind-Body Techniques: Practices such as yoga, tai chi, meditation, and biofeedback can help manage pain by reducing stress and promoting relaxation. A review of studies on yoga and back pain found that yoga can reduce pain in some cases.

- Alternative Therapies: Acupuncture and chiropractic care may offer pain relief for some individuals.

- Medical Marijuana or CBD: In states where it is legal, medical marijuana or cannabidiol (CBD) products are sometimes used for pain management, although evidence for effectiveness varies.

In conclusion, opioid use can be safe for some patients for short-term use, if prescribed and monitored by a doctor. However, because of the risks, patients should first attempt to manage their pain in ways that do not require opioid use. This is especially true for those suffering from chronic back pain, since long-term opioid use significantly increases the risk of addiction and overdose.

It’s important to consult with a healthcare provider to determine the most appropriate treatment for your back pain based on your specific condition and medical history. Receiving definitive treatment for an underlying spinal condition before symptoms become chronic can alleviate pain and obviate the need for opioids.